Managing Adult Malnutrition

Managing Adult Malnutrition

Including a pathway for the appropriate use of

oral nutritional supplements (ONS)

Optimising Nutritional Care in Cancer

The prevalence of malnutrition in patients with cancer varies considerably (up to 83%); depending on cancer type, the stage of the disease and patient age17-18.

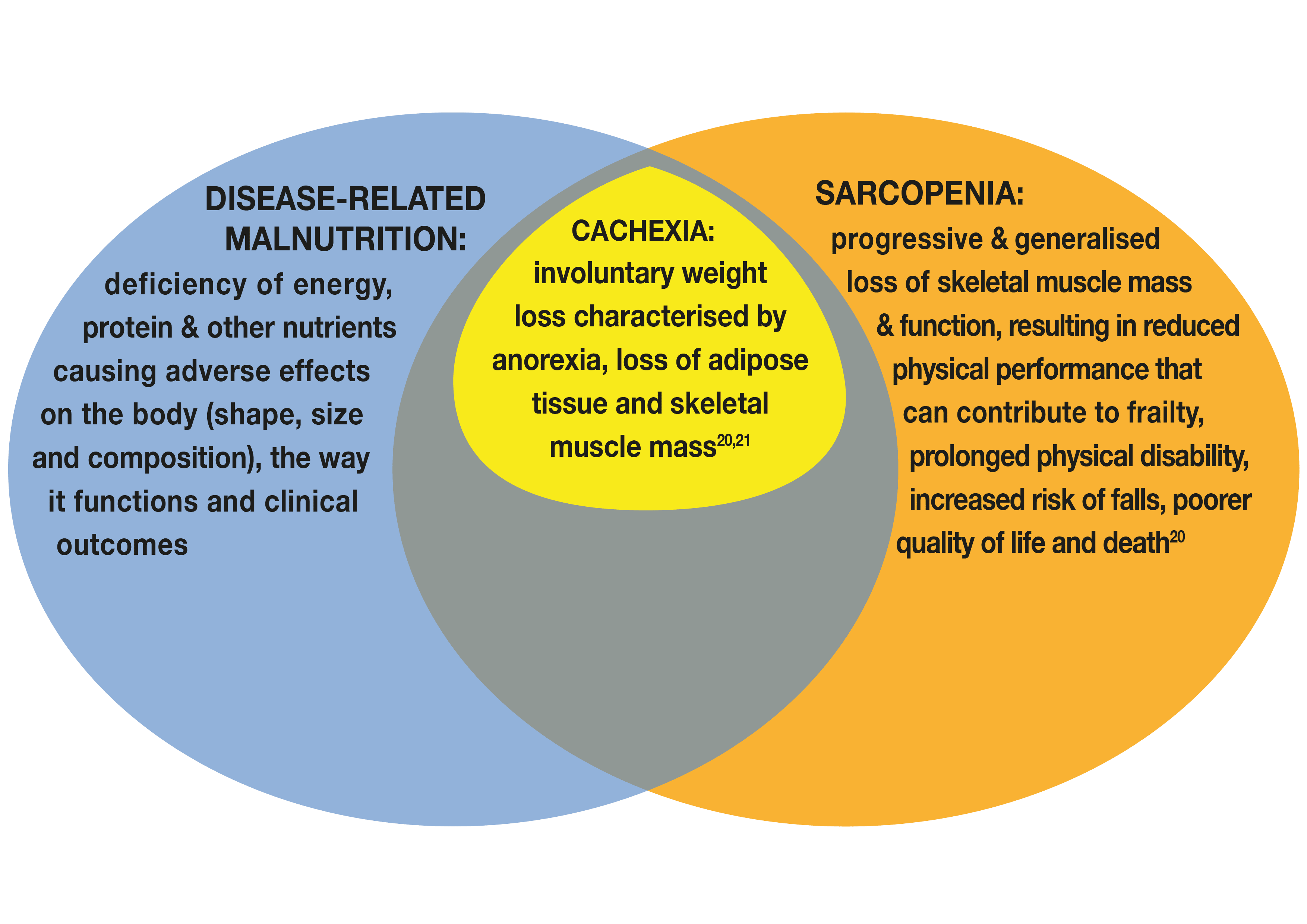

Figure 1 outlines the definitions of disease-related malnutrition, sarcopenia and cachexia and how they relate to one another.

The negative impact of malnutrition is well-documented and includes increased postoperative recovery times, increased risk of infections, longer hospital admissions, poorer response to treatment and diminished overall survival

The ‘Impact of Malnutrition in Cancer’ section (below) provides an overview of the negative sequelae associated with malnutrition.

Figure 1: The relationship between disease-related malnutrition, sarcopenia and cachexia

Malnourished patients with cachexia and/or sarcopenia have a higher risk of treatment-related toxicity, treatment discontinuation, poor response to treatment (including surgery), lower activity level, impaired quality of life (QoL) and poorer prognosis21.

| Immune function impairment | Weight loss negatively affects the immune competence of a patient12,22 |

| Reduced performance status | Malnutrition and skeletal muscle mass loss in cancer patients are associated with reduced functional capacity23,24 |

| Depression, anxiety | Malnutrition and skeletal muscle mass loss in cancer patients are associated with psychosocial symptoms23,25 |

| Fatigue | Fatigue is common in patients with cancer and can hinder the purchase and preparation of food and affect appetite22. Low levels of essential nutrients e.g. iron (ferritin), vitamin D or magnesium can exacerbate or contribute to fatigue – levels can be checked when bloods are taken and corrected through targeted supplementation26. |

| Decreased response to chemotherapy and increased chemotherapy-induced toxicity | Loss of skeletal muscle mass has a detrimental effect on patients’ response and tolerance to anti-cancer treatment27-32 |

| Increased frequency and severity of complications |

|

| Reduced quality of life |

|

| Reduced survival time | Malnutrition and skeletal muscle mass loss are associated with increased mortality39-40 which is also observed in those who are overweight or obese41 |

| Increased demands on health services, increased cost of care |

|

The nutritional status of patients will vary from patient to patient at diagnosis and at points in their journey. Improving nutritional care for people with cancer is reliant on 3 main steps18,27,45:

- Early screening of all patients with cancer for nutritional risk.

- Assessment of nutrition-related issues, functional measures, physiological measures

- Using multimodal nutritional interventions with individualised plans, including care focused on optimising nutritional intake and physical activity.

Nutrition Screening

Regular nutritional screening can be undertaken using a tool such as ‘MUST’

MUST: FURTHER INFORMATIONAssessment

Questioning for the presence of diet-related issues can help to identify malnutrition risk and diet-related distress that can then be managed at the earliest opportunity46. There are a variety of tools that have been validated for use in oncology patients10, 47-49. They generally take into account dietary intake, diet-related issues (nutrition impact symptoms), weight and weight loss over time18,27. A variety of tools are available including SUBJECTIVE GLOBAL ASSESSMENT (SGA) and the PATIENT GENERATED SUBJECTIVE GLOBAL ASSESSMENT (PGSGA). Some may be more suitable than others depending on your healthcare setting.

The Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM) recommends a two-step approach for the diagnosis of malnutrition, this involves screening to identify risk status by the use of any validated screening tool, and then an assessment for diagnosis and the grading of the severity of malnutrition50. Phenotypic characteristics such as unplanned weight loss, low body mass index, and reduced muscle mass should be considered alongside etiologic criteria such as reduced food intake, absorption and inflammation or disease burden. To diagnose malnutrition at least one phenotypic criterion and one etiologic criterion should be present50.

Regardless of the tool used a thorough symptom assessment (see Nutrition Impact Symptoms and their Management section) can identify factors contributing to poor intake and malnutrition.

Unintentional weight loss should alert healthcare professionals to take action and undertake further assessment to determine the severity of weight loss and whether the weight lost is muscle or adipose tissue (fat). Preserving muscle not just weight, is considered a key goal in cancer in improving outcomes such as response to treatment and preserving quality of life45.

In hospital, sophisticated methods to assess body composition, including muscle mass, may be available e.g., DEXA scanning, CT scans, bio-impedance. Where these are not available, functional measures such as sit to stand, walk test, hand grip strength and patient directed questions about reduced ability to perform daily activities or changes in fitness, can help to indicate if loss of muscle mass and strength has occurred and guide decisions on treatment.

STEP BY STEP INSTRUCTIONS for conducting the sit to stand, 4 stage balance test and timed up and go test – under the 'functional assessments' section.

Instructions on administering a TWO MINUTE WALK ENDURANCE TEST and a FOUR METRE WALK GAIN SPEED TEST

SARC-F QUESTIONNAIRE - a five item questionnaire that helps determine the likelihood of sarcopenia.

KEY POINT:

Detecting nutritional issues at an early stage can help minimise or prevent deterioration in nutritional status and loss of muscle mass that may be resistant to intervention or irreversible later on. Members of the healthcare team should be trained to regularly observe and evaluate nutritional intake, record changes in weight and body mass index (BMI) and act on the findings, at cancer diagnosis and repeatedly thereafter along the patient journey, depending on the stability of the clinical situation.

Identifying the underlying factors contributing to a reduced dietary intake that can be managed or reversed to avoid further deterioration in nutritional status is a key element of nutritional care. The section on nutrition impact symptoms and their management below illustrates common problems experienced by patients along with practical tips, and links to resources, that can be used to help patients and families.

Advice should take into account the holistic needs of the patient, discussing with the patient and family members or carers, what is most bothersome and what matters to them. Issues identified, advice given and actions taken or recommended, should be documented in the patient record and communicated to members of the healthcare team particularly as the patient moves across care settings51, 52.

The information below contains advice to discuss with patients relating to prehabilitation.

The information below contains advice to discuss with patients relating to prehabilitation.

An advice sheet to share with patients is available for download:

Prehabilitation - getting ready for treatment

Prehablitation (prehab) is about getting your body ready for treatment, whether that is surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy or immunotherapy. It can involve improving your nutrition, physical fitness and psychological wellbeing. At your diagnosis your healthcare team may screen you for any problems in these three areas. Taking action early to address any problems can help you tolerate your treatment, have fewer side effects or cope better. In turn this can get you through your treatment journey and help you recover.

Some of the things you might wish to consider in relation to your diet in the weeks running up to treatment are outlined below:

Being as well-nourished as possible before you start your treatment can help you deal with problems that might arise along the way. Enjoying what you eat is important too.

A balanced diet needs to include food from all the food groups to make sure your body works well, these include beans, pulses, fish, eggs, meat and other proteins, starchy foods, fruit and vegetables and dairy foods such as milk, yoghurt and cheese or dairy alternatives.

Ideally you should eat enough calories (energy) and enough protein to keep your weight steady and keep as strong as possible. If you are underweight or have lost weight unintentionally then you may be advised to try and gain a little weight.

Even if you are overweight, losing weight at this time may not be recommended but instead ensure you avoid gaining more excess weight.

A balanced diet includes:

- enough calories to give you the energy to perform your everyday activities

- enough protein to keep your muscles strong and your immune system working. This is important before and during treatment - if you are wondering if you are eating enough protein see more information on high protein foods in the leaflet ‘Protein, why it is important and where to find it’

- five portions of fruit and vegetables each day which provide fibre and vitamins and minerals – one portion is 3 tablespoons of vegetables or one medium piece of fruit or two smaller pieces of fruit or a handful of small fruits such as grapes or strawberries. A glass of fruit juice or smoothie can count as one of your five a day

- starchy foods such as potatoes, rice, noodles, pasta, bread, cereals – these provide energy but also fibre especially when wholegrain

- plenty of fluids to keep you hydrated – aim to drink between 1.5 and 2.5 litres of non-alcoholic fluids a day and enough to keep your urine pale straw colour

To help understand your individual needs the Malnutrition Pathway team has produced 3 leaflets that give further advice on diet:

- Eating Well - this leaflet gives advice on how to eat well and keep as healthy as possible:

- Your Guide to Making the Most of Your Food - this leaflet provides some simple ideas on how you can get the most nutrition from the food you are eating and is helpful if you have a poor appetite, have lost weight unintentionally or are underweight and need to increase your energy and nutrient intake:

- Nutrition Drinks (known as Oral Nutritional Supplements): this leaflet is for those people who have been prescribed oral nutritional supplements by their healthcare professional. It gives general advice on getting the most from these supplements, for example advice on cooking with supplements and storage:

- You may find it helpful to make daily meal plans so you can create a helpful shopping list with foods you would like to include to meet your needs

- As you might have ‘off days’ when your appetite is poor or you are lacking energy consider stocking up your freezer and store cupboard with easy to prepare or easy to eat and foods and snacks (the British Dietetic Association has produced a helpful leaflet on this and although it was created for older people it is a great source of ideas for anyone preparing for treatment:)

- Keep as physically active as possible – continue to do the activities you enjoy especially those that help maintain your strength, for some that might be a daily run or cycle, for others it might be a gentle walk around the neighbourhood or garden. Try not to sit for long periods of time as this may lead to muscle loss and tiredness

- If you are diabetic, ensure you check your blood sugar regularly and speak to your diabetes nurse or GP about how you might best manage your condition during your treatment

Nutrition Impact Symptoms - Common symptoms and issues interfering with the ability to eat and drink and advice to consider.

Below is a list of common nutrition impact symptoms. Click on each issue for advice for patients and their families. Downloadable pdfs to print off are available at the bottom of relevant sections.

Seek advice from a doctor, nurse specialist, oncology pharmacist or the general care team when necessary.

Issues/symptoms:

Advice to consider

- If your appetite is poor try to eat 3 small nutritious meals and 3 small snacks and / or nourishing drinks each day. Eat your favourite foods whenever you feel like them

- Try to eat foods rich in protein as this will help to maintain muscle. Further information on protein rich foods can be found in the leaflet PROTEIN - WHY IT IS IMPORTANT AND WHERE TO FIND IT

- If you have lost weight you may need to adjust your usual diet. This might include swapping to full fat milk in place of semi-skimmed milk, mixing grated cheese, milk powder, ground nuts, plant protein, or cream into foods such as sauces, mashed potato, and soups

- Keep snacks within easy reach - cheese and biscuits, chocolate, cakes, crisps, dried fruit and nuts, peanut butter on toast, falafel, breadsticks and dips are a good way to get extra calories and protein throughout the day

- Have nourishing drinks e.g. hot chocolate, malted drinks, milkshakes and smoothies (including those made with plant-based alternatives), in between meals

- Try not to drink too much fluid with meals as this might fill you up too quickly but do drink enough fluids between meals to keep hydrated. Except for alcohol, all fluids count including nourishing drinks

- Further advice on adding additional calories to your diet can be found in the leaflet YOUR GUIDE TO MAKING THE MOST OF YOUR FOOD

- If you are vegetarian, vegan or choose a plant-based diet you can read more about nourishing food choices at the following links: HOW DO I HAVE A NOURISHING PLANT BASED DIET or on THE VEGAN SOCIETY WEBSITE - "THRIVING RECIPES"

- You may need to be prescribed an oral nutritional supplement to help avoid further weight loss and to minimise any loss of muscle and function. If you are prescribed an oral nutritional supplement these should usually be consumed in addition to your diet. Further advice is available in NUTRITION DRINKS (known as Oral Nutritional Supplements)

- The Patient’s Association has produced two useful factsheets. The first helps to identify if you are at risk of malnutrition and the signs to look out for. The second describes how oral nutritional supplements, including those prescribed, can be used as a treatment for malnutrition, along with tips on where to get advice and further information to ensure that your nutritional health is the best it can be: GO TO PATIENT'S ASSOCIATION WEBSITE

Advice to consider

- If you have lost weight and have dentures, you may find the dentures no longer fit properly, if this is the case try and arrange a visit to a dentist as soon as you can

- If your mouth is dry or sore, ask a healthcare professional to check that you don’t have an oral infection. They may also be able to recommend a treatment to soothe the discomfort

- Try eating soft, easy to chew, moist foods with added sauces. For example casseroles, slow cooked meats, fish pie, Shepherd’s pie, chopped chicken in a sauce, vegetable bakes, minced meat dishes, soya based/Quorn mince dishes, risotto, softly cooked pulses in sauce

- Soups are soothing and easy to eat but can be low in energy and nutrients. Creamy ones that contain meat, chicken, beans or pulses may be more nutritious Add grated cheese to boost the energy and protein content.

- For sweet options try mashed or stewed fruit, fruit compote with yogurt, custard, evaporated milk, ice cream, sorbet, dairy or coconut milk rice pudding, milk shakes, panna cotta, creme caramel, milk jelly, soft cheesecake and tiramisu

- You may find it easier to eat smaller meals more frequently

- If your mouth is sore:

- It may be best to avoid spicy and hard crunchy foods

- Cold food and drinks may be comforting e.g. chilled water, ice cream, ice lollies. Drinking through a straw may help

- Acidic foods such as vinegar, pickles, tomatoes, oranges and lemons may be best avoided. Try mango, peach, blackcurrant or apple juice instead of citrus juices

- Very salty foods, such as crisps, salted nuts and beef drinks, may irritate soreness

- If you are breathless, cool air blowing directly onto or across your face may help - sit by an open window or use a small, handheld fan

Advice to consider

Loss of taste/taste changes are often temporary, occurring for days or weeks, but in some cases can continue for months and cause considerable distress and loss of enjoyment in eating and drinking. Foods can taste odd, metallic, too sweet or salty or unusually bland (have little taste). Some people find they are unable to tolerate strong flavours and actually prefer more bland food and drinks. As everyone's experience differs we have included a list of tips below for you to select the ones that suit your needs:

- Enhance taste with sauces, marinating, trying new foods, adding herbs, spices or zest

- Add herbs and spices, celery, onion, cinnamon, ginger or garlic to dishes for a stronger flavour

- Strong condiments may be useful like mustard, vinegar, lemon juice and dressings for salad

- Cold foods may be better or different textures; quiche, hummus, yogurt, crunchy nuts or seeds as a topping or crispy crackerbreads

- Try alternative protein sources – if you find meat unappetising opt for cheese, dairy foods, nuts, eggs, beans, lentils, tofu, Quorn

- If you are put off by strong flavoured foods try blander options such as milky porridge, cheesy mashed potatoes, creamed chicken in white sauce with rice

- Retry foods, including those that are less familiar or that may not have been enjoyed in the past as tastes may change over time

- Drink plenty of fluids (especially between meals) and keep your mouth clean - try alternatives such as herbal or peppermint tea, milk, fruit juices or flavoured squash

- Having a dry mouth can affect your taste. Adding sauces and choosing moist foods can help as can taking regular sips of fluid and drinking enough fluids between meals and keeping your mouth clean- you can find further ideas on managing in the dry mouth section above.

Swallowing issues can result from the cancer itself or the treatment. Some medications can cause a dry mouth or sleepiness that make eating and drinking more difficult.

Advice to consider

- Assess your current medication to ensure this isn’t causing side effects such as dry mouth which makes chewing and digestion more difficult - speak with your pharmacist if you have any concerns

- The NICE clinical guideline (CG32)51 identifies a number of obvious indicators of swallowing issues (dysphagia) such as painful chewing or swallowing, difficulty controlling food or liquid in the mouth, drooling, hoarse voice, coughing or choking before, during or after swallowing, nasal regurgitation or unintentional weight loss along with some less obvious indicators such as a change in respiration pattern, unexplained temperature spikes, dry mouth, heartburn, frequent throat clearing and recurrent chest infections

If swallowing is a problem, your GP can refer you to a speech and language therapist and/or Dietitian for a further assessment. You may be advised to change the consistency of food and drinks to make swallowing easier and safer. A thickener to add to drinks may be prescribed. These general tips may also help:

- Ensure you are sitting up straight, preferably at a table, whilst eating

- Tiredness may increase risk of swallowing difficulties; consider adjusting meal times so you eat when you aren’t as tired

- Eat smaller portions more often

- Changing the texture of foods may make them easier to chew and digest; chop, mash or puree foods before serving

- If you have been advised to have pureed food try to make sure food looks as appetising as possible. A number of home food delivery services offer pureed meals for people with swallowing difficulties, ask your healthcare professional for further information if you feel this would be useful

- Just because a food is easy to puree it might not be to your taste so ensure you are eating food you like

- A speech and language therapist or nurse may be able to advise you on exercises to help strengthen the muscles you use when swallowing

- Equipment such as special cups and spoons designed to place and limit the volume of food in the mouth to make it easier for you to swallow may be available; a speech and language therapist or occupational therapist can offer further advice

Further information on swallowing problems (dysphagia) is available: DYSPHAGIA: A HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONAL FACT SHEET

NB: If the symptoms are severe or do not settle within a few days consider speaking to a dietitian or your healthcare team.

Advice to consider

Changes in bowel habit and stools can arise as a result of the cancer, be a side effect of treatment (even some months after treatment has finished) or arise as a result of an infection.

- If you are constipated try to:

- Eat regular meals

- Eat foods rich in fibre such as whole-wheat breakfast cereals, oat based breakfast cereals with added nuts, seeds and dried fruit, wholemeal bread, wholewheat pasta, brown rice, fresh fruit and vegetables

- Keep hydrated by drinking plenty of fluids (Note: If you increase your fibre intake you need to ensure you are drinking lots of fluids or your constipation will get worse. All fluids count: soups, tea, coffee, milk, juice, squash, water etc.)

- Try softer texture foods such as lentil soup, pea and mint soup, dahl, hummus, bean stew, bean dips, porridge, overnight oats, softened Weetabix, stewed or baked fruit

- Try taking a small glass of prune juice or fig syrup, or up to 5 ‘ready-to-eat’ dried prunes or apricots

- Consider adding some linseed (ground or seeds) to soups, salads, mix into cereal or yogurt. Start with one dessertspoonful a day and build up to two dessertspoonfuls a day after 3 days

- Gentle exercise and pelvic floor exercises can also help bowel function

- If you have diarrhoea:

- Drink plenty of fluid each day to replace what you are losing but avoid or minimise alcohol and caffeinated drinks

- Eat small, frequent light meals made with easy to digest foods such as white fish, poultry, low fat dairy produce, well cooked eggs, white bread, pasta, rice

- Some people find reducing the fibre in their diet e.g. switching from wholegrain bread to white bread and from wholegrain cereals to lower fibre cereals such as cornflakes or Rice Krisipes can help. Others find taking softer forms of fibre e.g. porridge rather than Weetabix or stewed fruit rather than fresh, is helpful. Seek further advice from a dietitian

- Be aware that fatty foods and spicy foods may make diarrhoea worse

- Eat your meals slowly

Advice to consider

- Being in pain can affect your appetite or make it difficult to eat. Seek guidance from your care team about identifying the cause of your pain and managing it

- Poor appetite and weight loss can be caused by anxiety or depression, or can contribute to it. Speak to your healthcare professional about referral to services which can support you

Advice to consider

If smells of cooking are bothering you and make you feel less hungry, the following ideas might help:

- Consider using ready meals to limit cooking smells

- Some people find trying cold foods instead of hot foods helps - they tend to have less strong smells and it eliminates cooking smells

- Ask someone to cook whilst you are in a different room so you aren’t exposed to the smells

- Use lids on pans when cooking to reduce cooking smells

- Turn on cooker vents or open windows so cooking smells don’t linger

- It is good to get out into the fresh air for your well-being emotionally and physically – try a gentle walk around your garden or neighbourhood

Advice to consider

Patients should be under the care of a stoma care nurse – further information can be found HERE

Advice to consider

Heartburn is a burning feeling in the chest caused by stomach acid travelling up towards the throat (acid reflux). If it keeps happening, it's called reflux or gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD). The main symptoms of acid reflux are:

- a burning sensation in the middle of your chest

- an unpleasant taste in your mouth

Here are some suggestions to try to reduce heartburn and reflux:

- Avoid eating large meals; instead, eat little and often

- Fizzy drinks, caffeinated drinks, tomatoes, alcohol and fatty or spicy foods may make symptoms worse so try to minimise these foods

- Allow hot foods to cool a little and cold foods to warm a little at room temperature before consuming

- Sit at the table to eat and avoid bending over for a couple of hours after eating a meal

- Try not to fill up on fluids when you are eating. Instead try to take fluids between meals to keep hydrated

- Avoid lying down for at least 2 hours after eating

- Elevate the head of your bed - if you regularly experience heartburn while trying to sleep, place wood or cement blocks under the feet at the top of your bed so that the head end is raised by 6 to 9 inches. If you can't elevate the head of your bed, you can insert a wedge between your mattress and bed base or purchase a wedge pillow to sleep on to elevate your body from the waist up

- Talk to your healthcare team about medications that may help e.g. proton pump inhibitors on prescription or over the counter medications

If you are feeling sick or being sick:

Nausea and vomiting can be treated well using antiemetic drugs speak to your doctor or pharmacist about what is best for you

- Don't force yourself to eat a meal if the nausea is bad. Consider taking snacks/nibbles

- Eat frequent small snacks, particularly when you are feeling hungry, rather than sticking to meal times

- Eat dry food, such as toast, savoury or plain crackers or breakfast bisuits if you are able to

- Eat light foods such as soup, jelly and ice cream, greek yogurt and honey or creme caramel

- Consume nourishing drinks to obtain extra calories and protein (e.g. hot chocolate, milkshakes)

- Eat cold meals if the smell of cooking makes you feel sick or get someone else do the cooking for you

- Avoid being near smells of cooking as these may make you feel worse before your meal. Eat in a separate room from where the food is cooked if possible

- Avoid fried and fatty foods and those with a strong smell

- Ventilate the room you are eating in or sit near an open window if you can

- Sit upright at a table to eat and stay sitting for a short time after the meal to help your food to digest properly

- Try some of the following foods and drinks to see if they help - ginger biscuits, ginger cordial or ginger ale, ginger or peppermint tea, boiled fruit drops, fizzy drinks such as lemonade and cola (allow to go a little flat). Sipping slowly through a straw may also help

- Anxiety can make nausea worse, so try to make meal times calm

Advice to consider

Untreated and ongoing anaemia can impair immunity, affect energy levels, appetite and exacerbate fatigue. Ask your healthcare team to help identify the cause and treat if appropriate:

- Ensure adequate iron and vitamin C intake:

- Good sources of iron include - red meat, oily fish, eggs, beans, pulses, nuts, seeds, fortified cereals, dried figs, dried apricots, raisins and green leafy vegetables such as spinach, watercress and kale

- As Vitamin C enhances the uptake of iron include foods rich in Vitamin C along with iron rich foods. Good sources include citrus fruits, blackcurrants, blackcurrant juice, red and green peppers, green leafy vegetables, broccoli, and potatoes. For example a try a glass of orange juice alongside scrambed egg

Advice to consider

This can arise in pancreatic cancers, pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy should be initiated and titrated according to food intake, symptoms and stool type. Further information can be found HERE

Advice to consider

The Royal College of Occupational Therapists provide so useful advice on conserving energy and pacing activity to manage fatigue: MORE

If you are constantly tired, try some of the energy saving ways from the list below to help you eat a balanced diet with sufficient calories and protein:

- Eat softer foods that are easier to swallow

- Buy ready meals to reduce the amount of energy required to cook

- Consider buying items that lessen the burden of cooking - for example marinated chicken to which you just have to add the vegetables to the main part of the meal

- Prepare food when your energy levels are at their best, this might be in the morning. Keep a stock of frozen vegetables in the freezer to reduce the amount of preparation required for meal times

- Using a slow cooker or preparing a casserole means you can prepare the meals ahead of when you might eat them. If you make extra amounts you can freeze portions that can be eaten another day

- If you find you tire over the day you might wish to swap your cooked meals and snack meals around for example try a cooked breakfast or have your main meal at lunchtime and have a snack or bowl of cereal in the evening

- Ask friends and family to stock the freezer or fridge with portioned meals

- Order your shopping online and get it delivered

- Keep a stock of foods in your cupboard so you know you have some items in store to use if you are too tired to shop or wish to shop less frequently'. Useful store cupboard ideas can be found HERE

- Find out what assistance is available locally via social services such as meals on wheels, befriending services, help within the home, dining clubs

Note: If you are diabetic, ensure your diabetes is managed as well as possible as poor blood glucose control can make fatigue worse

Note: If you are diabetic, ensure your diabetes is managed as well as possible as poor blood glucose control can make fatigue worse

The Royal Surrey Hospital has produced a number of 2-3 minutes videos which aim to support oncology patients through treatment by answering some on the commonly asked questions about diet and cancer. Topics covered include:

What should I eat if:

- I just don’t feel like eating

- I am losing weight

- I am losing muscle and strength

- I find it difficult to swallow

- Food and drink do not taste right

- I have a sore mouth

- I have diarrhoea

- I am constipated

- I feel sick

- I have diabetes

There are also videos explaining how to fortify foods and how to incorporate nutritional supplement drinks into the daily diet if they have been prescribed.

Nutrition support and diet therapy can comprise dietary counselling, dietary modification (food fortification, texture modification), oral nutritional supplementation (ONS), enteral tube feeding (ETF) or parenteral nutrition (PN).

Although nutrition support is often required for cancer patients to prevent and manage malnutrition and sarcopenia and improve treatment efficacy; dietary advice may also alleviate the side effects of the cancer treatment, this dual effect helps improve quality of life53-55.

Nutrition support may need to be commenced at diagnosis, during prehabilitation, treatment or at any point throughout the patient journey. Care should be taken to ensure that nutrition support is not withdrawn at a time that it is still of benefit e.g. tube feeding is sometimes stopped as soon as a patient is able to eat and drink but if food intake is slow to increase or if it is anticipated that oral intake will be insufficient to meet requirements, nutrition support might need to be continued to support oral intake.

The European Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition has produced practical guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients45 MORE It recommends that the energy expenditure of patients with cancer should be similar to healthy individuals – ranging between 25 and 35 kcal/kg/day. Protein requirements should be above 1g/kg/day and if possible up to 1.5g/kg/day. More information on increasing protein intake can be found HERE

Aerobic and resistance exercise have been shown to be effective strategies to improve upper and lower body muscle strength56. Where feasible, physical activity should be encouraged alongside nutritional care. The more active patients are, the greater the benefits to overall mood, stress levels and long-term health57,58. Building in activity through small changes to daily routines and creating new habits can help; aiming to be active every day will bring about the best physical and mental health benefits. Any activity is better than none; even 10 minutes at a time can add up throughout the day and the week and provides a foundation to build upon.

In clinical practice, oral nutrition is the preferred route of choice if it is possible and feasible to take nutrition and fluid via this route. Dietary counselling, with or without ONS, may be necessary to compensate for reduced food intake, addressing the nutritional deficit to prevent deterioration in nutritional status and preserve function during treatment and beyond. In individual’s with poor appetite or a restricted ability to eat and drink, or in whom a rapid deterioration in oral intake is anticipated, ONS may need to be initiated early in their management in conjunction with dietary advice to avoid weight loss and irreversible deterioration in nutritional status and functional ability.

Dietary advice should be based on the issues presenting, those most bothersome to the individual, and should consider and address taste changes, swallowing problems, diarrhoea, constipation, eating when breathless or eating with a dry mouth (see section on nutrition impact symptoms and their management).

Providing timely advice on managing eating difficulties can alleviate concerns and nutritional issues, and can also play a significant role in helping to maintain socialisation, for example by supporting the patient to eat more comfortably with family members or friends. Individualised advice adapted to the patient’s circumstances can also empower a patient and their carers. Referral to a dietitian or healthcare professional with the appropriate experience should be offered particularly when problems are complex, or the patient does not gain improvement from first line advice.

In the late stages of cancer (advanced cancer), where appetite is very poor and weight gain is less likely or not possible, explaining why the issues are arising e.g. as a result of factors produced by a tumour, can go some way towards alleviating anxiety amongst patients and their carers59.

If an individual is following a special diet for another medical condition, such as heart disease, gastrointestinal conditions, diabetes or renal failure, has a colostomy or ileostomy, or is really struggling with eating, refer to a dietitian.

Dietary counselling by a skilled practitioner (e.g. dietitian) takes into account the patient’s habitual diet, diet history, medical history, clinical information, presence of medical conditions, cooking abilities, access to food, psychological, cultural, religious and social factors that influence food choice, to create a tailored individualised approach to nutrition.

It should be noted that in some areas access to dietitians can be limited - other members of the multidisciplinary team should therefore initiate advice where possible to optimise intake.

Nutritional intervention with ONS can improve energy and protein intake and reduce weight loss in cancer60-63, improve QoL in patients who are malnourished and may also result in cost savings 55,62,64,65. Systematic reviews and NICE Clinical Guidance (CG32) indicate the clinical efficacy and cost effectiveness of ONS in the management of malnutrition, particularly in those patients with a low Body Mass Index (BMI<20kg/m2) 51,54,65-67. ONS are energy-dense preparations which have demonstrated efficacy in improving nutritional outcomes when administered alongside dietary counselling18

There are a wide range of ONS styles (milkshake, juice, yogurt, savoury), formats (liquid, powder, pudding, pre-thickened), types (high protein, low volume, fibre containing,) energy densities (1-2.4kcal/ml) and flavours available to suit a wide range of patient needs. Most ONS provide approximately 300kcal, 12g protein and a full range of vitamins and minerals per serving68. Many patients requiring ONS can be managed using 1.5-2.4 kcal/ml. The amount of fluid in a standard ONS is approximately 200ml; however, for those with a small appetite and/or those who are breathless or who have difficulty drinking larger volumes of fluid, there are more concentrated supplements available which contain the same amount of nutrition, but in a lower volume e.g. 125ml rather than 200 ml. Further information on types of ONS available can be found HERE

When commencing ONS the considerations outlined below are important:

- Establish preferred flavours likes and dislikes e.g. milk or juice, sweet or savoury69 - several products have been developed which have sensory adapted flavours – these have a either a cooling or warming effect to stimulate some of the neural pathways where there is taste change

- Test preferences to help support compliance and reduce flavour fatigue with a prescribable ‘starter pack’

- Prescribe preferred product/flavour; 2 ONS/day (range 1-3/day) – see pathway for using ONS in the management of malnutrition70 HERE

- An initial prescription of 12 weeks with follow up every 1-3 months to monitor progress is recommended

- Ensure patient understands the importance of following the prescription

- Set clear, realistic goals with the patient (e.g. strength maintenance, prevent further weight loss) and ensure these are monitored

- Refer to a Dietitian where possible and particularly if ONS is the sole source of nutrition, is required long-term or patient has complex needs

- Modular ONS – that provide one or two nutrients – in either powdered or liquid format should only be used under dietetic supervision

- If the patient has diabetes their blood sugars may need to be monitored more closely if appropriate

- Low volume ONS may aid compliance71,72 and be better tolerated by patients who cannot consume larger volumes

- High protein requirements are recommended in cancer. High protein ONS may be appropriate for patients with some types of cancer – refer to a dietitian for further advice

- ONS with anti-catabolic and anti-inflammatory ingredients, in the form of essential amino acids or omega-3 fatty acids, may improve muscle protein synthesis (essential amino acids), and appetite, oral food intake, lean body mass and body weight (omega-3 fatty acids) in cancer patients18

If a patient has been discharged from hospital on a specific ONS, it is advisable to contact the dietetic department before switching products as there may be clinical and patient-centred reasons determining the choice as well as predicted adherence. Seek clarity from the professional recommending the ONS on the goals of treatment, likely duration and who is responsible for review and monitoring70. Whilst switching products may bring short term cost savings, the merit of this should be weighed against meeting the patient’s specific needs and supporting adherence to manage their malnutrition effectively, which can include avoiding hospital admissions/re-admissions and GP visits, all of which affects the patient’s QoL70, as well as increasing costs to the wider healthcare economy.

A number of nutritional supplements are available for self-purchase in supermarkets, pharmacies and online. Consider how accessible these may be to patients.

Before recommending powdered ONS to patients consider the following73:

- Clinical appropriateness

- Does the patient/carer have the physical ability to make up?

- Does the patient/carer have access to both a fridge and fresh milk?

- Does the patient have adequate storage for milk and boxes of powder?

- Can the patient/carer make up the powdered ONS as directed on the package to ensure safe handling practice?

If there is concern with the above, then a ready-made ONS may be more appropriate.

Further nutrition information and advice for patients with cancer and their carers is available to download HERE. This includes practical tips for eating and managing common symptoms, advice on managing a poor appetite and how to get the most out of oral nutritional supplements if they are prescribed.

Enteral nutrition (EN), or enteral tube feeding (ETF), is indicated if oral nutrition remains inadequate (less than <60% of nutritional requirements)19 despite nutritional intervention (nutritional counselling, ONS)18,20. Such inadequate intake may occur in patients with tumours that impair oral intake, digestion and absorption in the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract27. ETF may be delivered through trans-nasal (nasogastric or nasojejunal tube) or percutaneous endoscopic, radiologically inserted, surgical gastrostomy or jejunostomy route21. ETF may be given preoperatively, both European and American guidelines recommend immune-enhancing formulas in cancer patients undergoing major head-neck or abdominal surgery 8,54,74. Postoperatively, ETF is recommended for patients who are malnourished at the time of resection, in those who cannot reinitiate oral nutrition early, or in those who have inadequate food intake for more than 10 days21. All ETF patients should be under the care of a dietitian and ideally a nutrition nurse too.

Parenteral nutrition (PN) is indicated in patients receiving cancer therapy who are facing a period of over 7 days of inadequate energy intake when nutritional counselling, ONS or EFT are not feasible, contraindicated or are ineffective due to impaired GI functionality8,19,21,75. PN is administered intravenously, requiring a catheter in order to administer nutritional preparations. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommend that PN should be introduced progressively, closely monitored and should cease as soon as a patient has received their nutritional recommendations orally or enterally51.

PN may be administered at home (HPN), in suitable patients in whom their cognitive and physical wellbeing, life expectancy (over 2–3 months) and home environment has been assessed and deemed suitable19,27. HPN has a positive impact on health care costs, mainly by reducing the number and length of hospitalisations76.

While PN may improve patient QoL and functionality, its administration should be considered with caution. Routine use is strongly not recommended21 and all HPN patients should be under the care of a nutrition team.

For all patients

- Nutritionally screen at diagnosis & subsequent clinic visits with local/national tool e.g. ‘MUST’

- Consider nutrition impact symptoms (see section on nutrition impact symptoms and their management)

- Identify barriers impacting on nutritional intake, using a list of typical problems as a prompt (see section on nutrition impact symptoms and their management). Probe to determine the degree of distress associated with issues/symptoms, offer help and advice using resources available and refer to other HCPs as needed

- Offer patient information according to the issue (see section on nutrition impact symptoms and their management)

- Encourage good mouth care especially amongst individuals with a poor oral intake, or on a tube feed or parenteral nutrition (see section on nutrition impact symptoms and their management)

- Don’t delay referral to a Dietitian for more specialist advice e.g., refer patients at high risk of malnutrition without delay, and medium risk if of concern

- In all cancer patients if food intake is insufficient (<60% of three meals per day) nutritional status can rapidly decline and as such the use of ONS may need to be considered early in management to limit deterioration

- Ensure ongoing monitoring and regular reviews – check compliance to advice and adjust nutritional intervention as required to maximise intake

- Consider the need for monitoring (including self-monitoring) beyond treatment as diet-related problems, unintentional weight loss, and muscle loss can remain a problem in cancer survivors (see section on impact of malnutrition in cancer)

The Managing Adult Malnutrition in the Community pathway provides GUIDANCE AND RESOURCES that are appropriate for use in patients with cancer.

- Pressoir M, Desné S, Berchery D, Rossignol G, Poiree B, Meslier M, et al. Prevalence, risk factors and clinical implications of malnutrition in French Comprehensive Cancer Centres. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(6):966-71.

- Su H, Ruan J, Chen T, Lin E, Shi L. CT-assessed sarcopenia is a predictive factor for both long-term and short-term outcomes in gastrointestinal oncology patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Imaging. 2019;19(1):82.

- Kirov KM, Xu HP, Crenn P, Goater P, Tzanis D, Bouhadiba MT, et al. Role of nutritional status in the early postoperative prognosis of patients operated for retroperitoneal liposarcoma (RLS): A single center experience. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2019;45(2):261-7.

- Versteeg AL, Van Tol FR, Lehr MA, Oner CF, Verlaan JJ. Malnutrition in patients who underwent surgery for spinal metastases. Annals of Translational Medicine. 2019;7(10):213.

- Anker MS, Holcomb R, Muscaritoli M, von Haehling S, Haverkamp W, Jatoi A, et al. Orphan disease status of cancer cachexia in the USA and in the European Union: a systematic review. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2019;10(1):22-34.

- Maasberg S, Knappe-Drzikova B, Vonderbeck D, Jann H, Weylandt KH, Grieser C, et al. Malnutrition predicts clinical outcome in patients with neuroendocrine neoplasia. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;104(1):11-25.

- Sullivan ES et al, A national survey of oncology survivors examining nutrition attitudes, problems and behaviours, and access to dietetic care throughout the cancer journey. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN. 2021; 41: 331-339.

- Bozzetti F, Arends J, Lundholm K, Micklewright A, Zurcher G, Muscaritoli M, et al. ESPEN guidelines on parenteral nutrition: Non-surgical oncology. Clin Nutr. 2009;28(4):445-54..

- Better care through better nutrition: value and effects of medical nutrition - A summary of the evidence base” 2018. https://medicalnutritionindustry.com/files/user_upload/documents/medical_nutrition/2018_MNI_Dossier_Final_web.pdf

- Ravasco P. Nutrition in Cancer Patients. J Clin Med 2019; 8:1211.

- Isenring EA, Bauer JD, Capra S. The scored Patient-generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) and its association with quality of life in ambulatory patients receiving radiotherapy. European Journal of Clinician Nutrition 2003;57:305–309.

- Van Cutsem E, Arends J. The causes and consequences of cancer-associated malnutrition. European Journal of Oncology Nursing 2005;9:S51–S63. Suppl 2:S51-63.

- Tong H, Isenring E, Yates P. The prevalence of nutrition impact symptoms and their relationship to quality of life and clinical outcomes in medical oncology patients. Support Care Cancer 2009;17:83–90.

- Bauer J, Capra S, Ferguson M. Use of the scored Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) as a nutrition assessment tool in patients with cancer. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2002;56:779–785.

- Bozzetti F, Mariani L, Vullo SL et al. The nutritional risk in oncology: a study of 1453 cancer outpatients. Support Care Cancer 2012;20(8):1919-1928.

- Macmillan, Royal College of Anaesthetists, National Institute for Health Research Cancer and Nutrition Collaboration. Principles and guidance for prehabilitation within the management and support of people with cancer. 2020. bit.ly/3uqqrB0

- Caillet P, Liuu E, Raynaud Simon A, Bonnefoy M, Guerin O, Berrut G, et al. Association between cachexia, chemotherapy and outcomes in older cancer patients: A systematic review. Clinical Nutrition. 2017;36(6):1473-82.

- Arends J, Baracos V, Bertz H, Bozzetti F, Calder PC, Deutz NEP, et al. ESPEN expert group recommendations for action against cancer-related malnutrition. Clin Nutr. 2017;36(5):1187-96.

- de Las Penas R, Majem M, Perez-Altozano J, Virizuela JA, Cancer E, Diz P, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients (2018). Clin Transl Oncol. 2019;21(1):87-93.

- Muscaritoli M, Anker SD, Argiles J, Aversa Z, Bauer JM, Biolo G, et al. Consensus definition of sarcopenia, cachexia and pre-cachexia: joint document elaborated by Special Interest Groups (SIG) "cachexia-anorexia in chronic wasting diseases" and "nutrition in geriatrics". Clin Nutr. 2010;29(2):154-9.

- Caccialanza R, Pedrazzoli P, Cereda E, Gavazzi C, Pinto C, Paccagnella A, et al. Nutritional support in cancer patients: A position paper from the Italian Society of Medical Oncology (AIOM) and the Italian Society of Artificial Nutrition and Metabolism (SINPE). J Cancer. 2016;7(2):131-5.

- Arends, J., 2018. Struggling with nutrition in patients with advanced cancer: nutrition and nourishment—focusing on metabolism and supportive care. Annals of Oncology, 29, pp.ii27-ii34.

- Schwarz S, Prokopchuk O, Esefeld K, Groschel S, Bachmann J, Lorenzen S, et al. The clinical picture of cachexia: A mosaic of different parameters (experience of 503 patients). BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):130.

- Antoun S, Morel H, Souquet PJ, Surmont V, Planchard D, Bonnetain F, et al. Staging of nutrition disorders in non-small-cell lung cancer patients: utility of skeletal muscle mass assessment. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2019;10(4):782-93.

- Sanchez-Torralvo FJ, Contreras Bolivar V, Ruiz Vico M, Abuin Fernandez J, Gonzalez Almendros I, Barrios Garcia M, et al. Relation between malnutrition and the presence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with cancer. Clinical Nutrition. 2019;38(Supplement 1):S47.

- Tardy, A.L., Pouteau, E., Marquez, D., Yilmaz, C. and Scholey, A., 2020. Vitamins and minerals for energy, fatigue and cognition: A narrative review of the biochemical and clinical evidence. Nutrients, 12(1), p.228.

- Arends J, Bachmann P, Baracos V, Barthelemy N, Bertz H, Bozzetti F, et al. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin Nutr. 2017;36(1):11-48.

- Palmela C, Velho S, Agostinho L, Branco F, Santos M, Santos MP, et al. Body composition as a prognostic factor of neoadjuvant chemotherapy toxicity and outcome in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer. J Gastric Cancer. 2017;17(1):74-87.

- Aaldriks AA, Giltay EJ, Nortier JWR, Van Der Geest LGM, Tanis BC, Ypma P, et al. Prognostic significance of geriatric assessment in combination with laboratory parameters in elderly patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Leukemia and Lymphoma. 2015;56(4):927-35.

- Jarvinen T, Ilonen I, Kauppi J, Salo J, Rasanen J. Loss of skeletal muscle mass during neoadjuvant treatments correlates with worse prognosis in esophageal cancer: a retrospective cohort study. World J Surg Oncol. 2018;16(1):27.

- Loosen SH, Schulze-Hagen M, Bruners P, Tacke F, Trautwein C, Kuhl C, et al. Sarcopenia is a negative prognostic factor in patients undergoing transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) for hepatic malignancies. Cancers. 2019;11(10):1503.

- Gallois C, Artru P, Lievre A, Auclin E, Lecomte T, Locher C, et al. Evaluation of two nutritional scores' association with systemic treatment toxicity and survival in metastatic colorectal cancer: an AGEO prospective multicentre study. European Journal of Cancer. 2019;119:35-43.

- Cardi M, Sibio S, Di Marzo F, Lefoche F, d'Agostino C, Fonsi GB, et al. Prognostic factors influencing infectious complications after cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC: Results from a tertiary referral center. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2019;2019:2824073.

- Weerink LBM, van der Hoorn A, van Leeuwen BL, de Bock GH. Low skeletal muscle mass and postoperative morbidity in surgical oncology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2020 Jun;11(3):636-649

- Planas M, Alvarez-Hernandez J, Leon-Sanz M, Celaya-Perez S, Araujo K, Garcia de Lorenzo A. Prevalence of hospital malnutrition in cancer patients: a sub-analysis of the PREDyCES study. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2016;24(1):429-35.

- Lodewick TM, Van Nijnatten TJA, Van Dam RM, Van Mierlo K, Dello SAWG, Neumann UP, et al. Are sarcopenia, obesity and sarcopenic obesity predictive of outcome in patients with colorectal liver metastases? HPB. 2015;17(5):438-46.

- Daly L, Dolan R, Power D, Ní Bhuachalla É, Sim W, Fallon M, et al. The relationship between the BMI-adjusted weight loss grading system and quality of life in patients with incurable cancer. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2020;11(1):160-8.

- Lis CG, Gupta D, Vashi PG. Role of nutritional status in predicting quality of life outcomes in cancer – a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Nutritional Journal 2012;11:27.

- Abbass T, Dolan RD, Laird BJ, McMillan DC. The relationship between imaging-based body composition analysis and the systemic inflammatory response in patients with cancer: A systematic review. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(9).

- Zhang X, Tang T, Pang L, Sharma SV, Li R, Nyitray AG, et al. Malnutrition and overall survival in older adults with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Geriatric Oncology. 2019;10(6):874-83.

- Gruber ES, Jomrich G, Tamandl D, Gnant M, Schindl M, Sahora K. Sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity are independent adverse prognostic factors in resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. PloS one. 2019;14(5):e0215915.

- Ferrer E, Boulahssass R, Gonfrier S, Champigny N, Michel E, Francois E, et al. Guided geriatric interventions (GI) and nutritional status: A study from the PACA EST French cohort. Journal of Geriatric Oncology. 2019;10(6 Supplement 1):S96-S7.

- van Vugt JLA, Braam HJ, van Oudheusden TR, Vestering A, Bollen TL, Wiezer MJ, et al. Skeletal muscle depletion is associated with severe postoperative complications in patients undergoing cytoreductive surgery with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. Annals of surgical oncology. 2015;22(11):3625-31.

- Van Vugt JLA, Buettner S, Levolger S, Coebergh Van Den Braak RRJ, Suker M, Gaspersz MP, et al. Low skeletal muscle mass is associated with increased hospital expenditure in patients undergoing cancer surgery of the alimentary tract. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(10):e0186547.

- Muscaritoli et al. ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical Nutrition in cancer. Clin Nutr. 2021 May;40(5):2898-2913.

- Arrieta O, Ortega RMM, Villanueva-Rodriguez G et al. Association of nutritional status and serum albumin levels with development of toxicity in patients with advance nonsmall cell lung cancer treated with paclitaxel-cisplatin chemotherapy: a prospective study. BMC Cancer 2010;10:50.

- Benoist S & Brouquet A. Nutritional assessment and screening for malnutrition. J. Visc. Surg. 2015;152(Suppl. 1):S3–S7.

- Thompson K.L, Elliott L, Fuchs-Tarlovsky V, Levin R.M, Voss A.C, Piemonte T. Oncology Evidence-Based Nutrition Practice Guideline for Adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017;117:297–310.

- Ottery F. Definition of standardised nutritional assessment and interventional pathways in oncology. Nutrition. 1996;12:s15–s19.

- Cederholm T, et al. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition - A consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. Clin Nutr. 2019 Feb; 38(1):1-9.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Nutrition support in adults: oral nutrition support, enteral and tube feeding and parenteral nutrition. Clinical Guideline 32. 2006.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Quality standard for nutrition support in adults. NICE quality standard 24. November 2012

- Baldwin C, Spiro A, Ahern R et al. Oral Nutritional interventions in malnourished patients with cancer; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of National Cancer Institute 2012;104(5):371-385.

- Arends J, Bodoky G, Bozzetti F et al. ESPEN guidelines on enteral nutrition: non-surgical oncology. Clinical Nutrition 2006;25:245-259.

- Rivadeneira DE, Evoy D, Fahey TJ et al. Nutritional support of the cancer patient. Clinical Journal of Cancer 1998;48:69-80.

- Stene GB et al. Effect of physical exercise on muscle mass and strength in cancer patients during treatment – a systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013; 88: 573-593

- Christense, JF., Simonsen C, Hojman P. Exercise training in cancer control and treatment. Compr Physiol. 2018 Dec 13;9(1):165-205.

- Stout NL, Baima J, Swisher AK, Winters-Stone KM and Welsh J. A systematic review of exercise systematic reviews in the cancer literature (2005-2017). 2017 Sep;9(9S2):S347-S384

- Cooper C, Burden S T, Cheng H, & Molassiotis A. Understanding and managing cancer-related weight loss and anorexia: insights from a systematic review of qualitative research. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle. 2015; 6(1): 99–111.

- Percival C, Hussain A, Zadora-Chrzastowska S et al. Providing nutritional support to patients with thoracic cancer; findings of a dedicated rehabilitation service. Respiratory Medicine 2013;107(5):753-761.

- Burden ST, Hill J, Shaffer JL et al. An unblended randomised controlled trial of preoperative oral supplements in colorectal cancer patients. Journal Human Nutrition and Dietetics 2011;24(5):441-448.

- Lee H, Havrilla C, Bravo V et al. Effect of oral nutritional supplementation on weight loss and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube rates in patients treated with radiotherapy for oropharyngeal carcinoma. Support Cancer Care 2008;16(3):285-289.

- Stratton RJ, Green CJ, Elia M. Disease-related malnutrition: an evidence-based approach to treatment. Walligford:CABI Publishing; 2003.

- Isenring EA, Bauer JD, Capra S. Nutrition support using the American Dietetic Association medical nutrition therapy protocol for radiation oncology patients improves dietary intake compared with standard practice. Journal of American Dietetic Association 2007;107(3):404-412.

- Elia M, on behalf of the Malnutrition Action Group (BAPEN) and the National Institute for Health Research Southampton Biomedical Research Centre. The cost of malnutrition in England and potential cost savings from nutritional interventions (full report). 2015. http://www.bapen.org.uk/pdfs/economic-report-full.pdf

- Garg S, Yoo J, Winquist E. Nutritional support for head and neck cancer patients receiving radiotherapy: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 2010;18(6):667-677.

- Stratton RJ, Elia M. A review of reviews. A new look at the evidence for oral nutritional supplements in clinical practice. Clinical Nutrition Supplements 2007;2:5-23.

- British National Formulary. https://www.medicinescomplete.com/about/publications.htm

- Haan et al. Self-reported taste and smell alterations and the liking of oral nutritional supplements with sensory-adapted flavors in cancer patients receiving systemic antitumor treatment. Suppor Cancer Care 2021 Oct; 29(10):5691-5699 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33629188/

- Holdoway et al. Managing Adult Malnutrition in the Community. 2021. https://www.malnutritionpathway.co.uk/library/managing_malnutrition.pdf

- Nieuwenhuizen WF et al. Older adults and patients in need of nutritional support: review of current treatment options and factors influencing nutritional intake. Clin Nutr 2010; 29(2):160-169.

- Hubbard GP et al. A systematic review of compliance to oral nutritional supplements. Clinical Nutrition 31 (2012), pp.293-312.

- Mulholland P, McKnight E, Prosser J. Audit of compliance with NI formulary for oral nutritional supplements in South Eastern Trust. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN. 2019; 29: 282–283 https://clinicalnutritionespen.com/article/S2405-4577(18)30716-2/pdf

- Weimann A, Braga M, Harsanyi L, Laviano A, Ljungqvist O, Soeters P, et al. ESPEN guidelines on enteral nutrition: Surgery including organ transplantation. Clin Nutr. 2006;25(2):224-44.

- August DA, Huhmann MB, American Society for P, Enteral Nutrition Board of D. A.S.P.E.N. clinical guidelines: nutrition support therapy during adult anticancer treatment and in hematopoietic cell transplantation. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2009;33(5):472-500.

- Santarpia L, Pagano MC, Pasanisi F, Contaldo F. Home artificial nutrition: an update seven years after the regional regulation. Clin Nutr. 2014;33(5):872-8.

Resources

A selection of publications for use by healthcare professionals, patients and carers are available in the resources section of the website.

Support for Patients & Carers

A number of resources are available that have been developed to support patients and carers.

Specific support for common conditions

A number of resources are available that have been developed to assist healthcare professionals supporting patients at risk of malnutrition as a result of a specific condition. These include:

Further Information

We can be contacted regarding the malnutrition pathway materials and website